Don't Save BART's Rainforest: Water Intrusion in the Tunnels

Over four decades after construction, underground trickles and leaks are becoming more and more common. Engineers are exploring options for a more permanent fix to keep BART dry, but why’s it so wet in the first place?

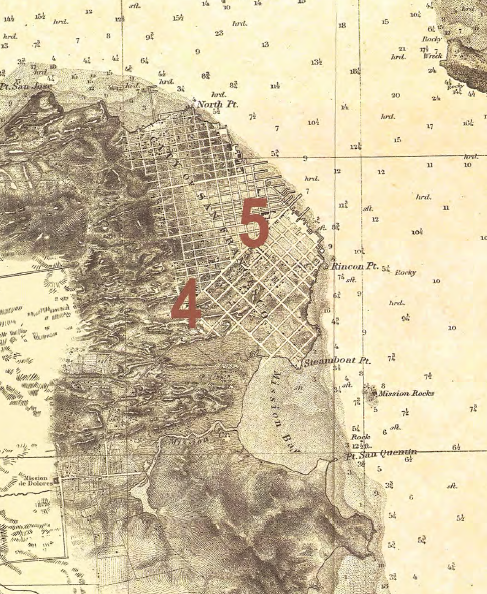

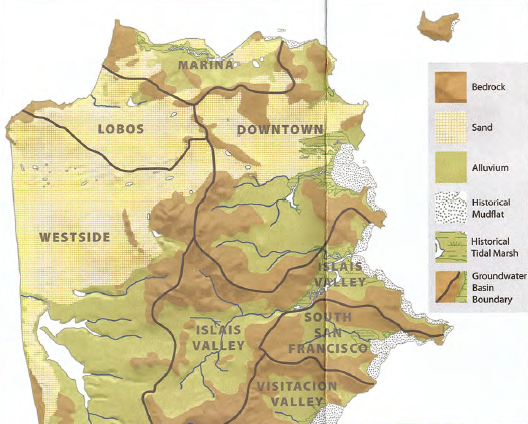

The problem all starts with location. Unlike the pricey real estate above, BART’s tunnels in downtown San Francisco are below the water table. This means either seawater or freshwater constantly seek to convert the section of trackway between Embarcadero and 16th Street/Mission Stations into a flume ride. One might think tunneling underground would create a watertight environment, but downtown San Francisco isn’t all rock—and not all rock is waterproof!

In fact, the amount of problematic water intrusion through the miles of trackway in downtown San Francisco has earned the whole area a dubious nickname – maintenance crews call it “the rainforest.”

Aging Takes Its Toll

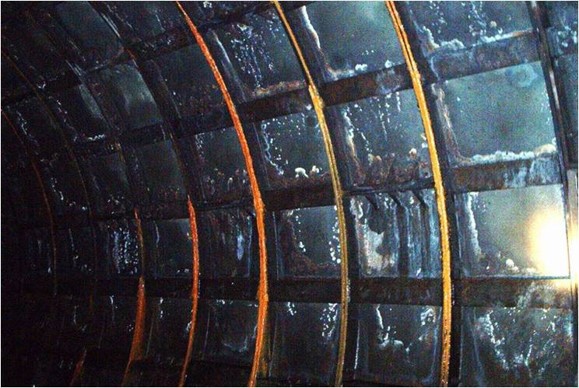

Back in the 1960s, after the tunnels were originally constructed, steel plates were set in place over the raw walls and bolted together. Caulk was then injected through holes in the plates to fill the space between the tunnel wall and the steel casing, sealing out liquid and insulating the finished tunnel. In the intervening decades, water slowly made its way through the caulking material and now leaks through many of the joints in the steel casing.

Back in the 1960s, after the tunnels were originally constructed, steel plates were set in place over the raw walls and bolted together. Caulk was then injected through holes in the plates to fill the space between the tunnel wall and the steel casing, sealing out liquid and insulating the finished tunnel. In the intervening decades, water slowly made its way through the caulking material and now leaks through many of the joints in the steel casing.

To fight these leaks, BART repair crews have been repacking the joints here and there over the years with a waterproofing compound. However, the compound degrades relatively quickly and must be checked often.

So why not just build drains in the floor, pump the water away, and call it a day?

First of all, this is a huge work area. BART already has pumps installed in the lowest tunnels near the largest and highest-volume underground streams such as at Powell Street Station.

Second, draining too much water from the whole downtown area could cause Market Street to sink (or possibly collapse).

Third, constant humidity in the tunnels isn’t something you really want to be there at all. Condensation builds on the rails, then as our fully-loaded trains roll over the liquid it can be forced into the steel itself and create micro fractures.

In constantly wet conditions, these micro fractures can grow and grow – the same way a pothole forms as cars run over the same weak spot in the road over and over. Eventually, these microscopic imperfections can actually cause the rail to break. Commuters may recall this very thing happening last May through a section of track in the rainforest—the broken rail snarled traffic in downtown San Francisco for hours, with delays lasting late into the evening commute. Nobody wants a repeat of that scenario.

In constantly wet conditions, these micro fractures can grow and grow – the same way a pothole forms as cars run over the same weak spot in the road over and over. Eventually, these microscopic imperfections can actually cause the rail to break. Commuters may recall this very thing happening last May through a section of track in the rainforest—the broken rail snarled traffic in downtown San Francisco for hours, with delays lasting late into the evening commute. Nobody wants a repeat of that scenario.

What's BART's Plan?

A long-term solution to keep these hundreds of thousands of gallons of water out of BART is needed, and BART’s engineers believe it will likely come in the form of a naturally occurring, muddy substance first discovered in Wyoming called bentonite.

Bentonite is a clay compound, both environmentally-friendly and renowned for its utility in waterproofing tunnels for decades between applications. In fact, you may have already heard of it – people have been known to use it as a spa treatment, reportedly giving their skin a healthy glow.

But how much will all that repair and replacement work cost, and how will it be implemented? The answer is that it will cost quite a bit of money over a long period of time, as the scale of implementation is huge. It will require repairing miles of tunnel, with complicated engineering challenges at every turn.

Infrastructure bonds are major public investments for big construction projects (like tunnel repair), and function similarly to how homeowners would finance a roof replacement. With a roof, you can patch here and there over the years, but eventually the whole thing must be replaced—likely with equity taken from the home.

Similarly, the bones of BART—including assets beyond leaking tunnels such as eroded trackway and deteriorating electrical cabling—are decaying. Measure RR would raise $3.5 billion to help cover the cost of big-ticket repair projects, with the money statutorily dedicated to these capital improvements and protected by an independent audit committee.

Waterproofing our tunnels is definitely one of those big-ticket repair items, because keeping water out keeps you safe on the way to your destination. Plus, having dry tunnels lowers the cost of maintaining BART to taxpayers in the future. There isn’t a transit-themed catchphrase equivalent to “a stitch in time saves nine”—but if there were, it would be here!

Learn more about Measure RR by visiting bart.gov/betterbart, and see our plan to keep you moving around the Bay.