Transit is punk: Kamala Parks went from cofounding 924 Gilman Street to urban planning at BART

BART transportation planner Kamala Parks is pictured in photos from the 1980s to present. Black and white photos courtesy of Murray Bowles.

“Transit is punk,” according to Kamala Parks, Principal Station Planner at BART.

Parks, of all people, would know.

The transportation planner was a formative force in the Bay Area punk scene, particularly from the mid-1980s through the 1990s. This was an inflection point for punk, with bands like Green Day, Neurosis, and the Offspring making the leap from tiny scene venues to sold-out concert halls and stadiums.

These iconic bands have at least two things in common. All of them are graduates of one of the most legendary punk venues of all time – 924 Gilman Street in Berkeley, often called Gilman by the punk community – and Parks played an early role in their success.

Parks cofounded 924 Gilman – an all ages, collectively organized nonprofit music venue still going strong today – in 1986 as part of the MaximumRockNRoll ‘zine and collective spearheaded by Tim Yohannan. Getting the venue off the ground required wading through the leasing and zoning process, attending city hall meetings, and speaking with officials. The experience was Parks very first taste of urban planning, and it would come to serve her professionally many years later.

So, Green Day...well, Parks was their first-ever band manager. Neurosis and the Offspring? She booked their first two national tours. The Offspring were the first to bring her on tour as their road manager, the first of many tour managing roles she did for multiple bands.

When she wasn’t uplifting other bands, Parks was drumming for Cringer, the Gr’ups, Naked Aggression, and the aptly named Kamala & The Karnivores. If you saw the recent film Freaky Tales, you might have spotted a Kamala & The Karnivores patch stitched on the back of star Ji-young Yoo’s jacket.

“Parks is a networker of East Bay punk,” a 2017 profile of her proclaimed, noting that she unknowingly designed “what would become a blueprint for DIY scenes worldwide.”

A recent photo of Kamala Parks at Lake Merritt Station.

In sum, Parks is a punk legend.

Many of her BART coworkers have absolutely no idea. Rather, they know Parks from her planning efforts, like her work on BART's Transit-Oriented Development, her leadership on projects like Safe Trips to BART, and her role as the Station Area Planner from Orinda to Antioch.

“Some folks are surprised I’m a punk rocker. They say I don’t look like one,” Parks said. “But I don’t have to look it. It’s my people, it’s a way of being in the world.”

And transit, she said, is decidedly punk.

"When you’re a punk, you love efficiency, sustainability, democracy,” she said. “Transit fulfills all these things.”

Parks brings the spirit of punk to the workplace. When you’re a punk, if there’s an obstacle, you find a way to work around it. Low on resources? Figure it out. And most importantly, never take anything at face value, always question the status quo.

“As a planner, I’m constantly asking myself things like, is there a reason this is the way it is? Can we revisit this? Reimagine it?"

It’s a helpful vantage point for someone in her line of work. Crudely put, planners assess the present to construct the future. There’s a synergy with planning and punk, the music and movement known for holding a magnifying glass to the world and asking, “Why does it have to be like that?”

“You don’t buy into the mainstream narrative as much when you’re a punk,” Parks said.

Kamala Parks, pictured front right, circa late 1980s/early 1990s at a backyard gig in Pinole. Credit: Murray Bowles

Parks’ career was the least of her concerns as a free-spirited teenager growing up in Berkeley.

“I was not exactly an ambitious kid,” she said. “When I was young, I wanted to be a cashier. They seemed to know everything – the price of an apple, the cost of a can of corn. This was way before the scanner. You had to enter all the prices manually! But as soon as the scanner rolled out, my dream was quashed.”

Parks described her teenage years as “directionless.” She was a mediocre student at Berkeley High School, didn’t have a lot of friends or grand ambitions.

What she did have was music. Parks recalled the summer before 11th grade when her dad left her in the care of one of his students from Diablo Valley College while he was on sabbatical in Europe. He gave the college kid $500 for Parks’ care and keeping. Not long after dad hit the road, the young woman and her boyfriend decided to spend the summer in Mexico, leaving Parks to fend for herself.

“I came home from school one day and no one was home. But she had left the money on the table,” Parks recalled. “I immediately went to Telegraph [Avenue] and bought records and a Walkman. Needless to say, I spent that $500 in a very short amount of time.”

“Music,” she went on, “was the thing that saved me as a kid. I cared about it so much, and I was beginning to have this incredible community in the punk scene full of very smart, supportive people.”

But she had a bone to pick with Berkeley: All the cool live music venues in town were 21 and over. So 17-year-old Parks wrote a letter to the city council more or less asking, “What gives? There’s nothing for young people to do in this city. Why aren’t there any all-ages music venues?”

That was the genesis of the idea that would eventually give birth to 924 Gilman.

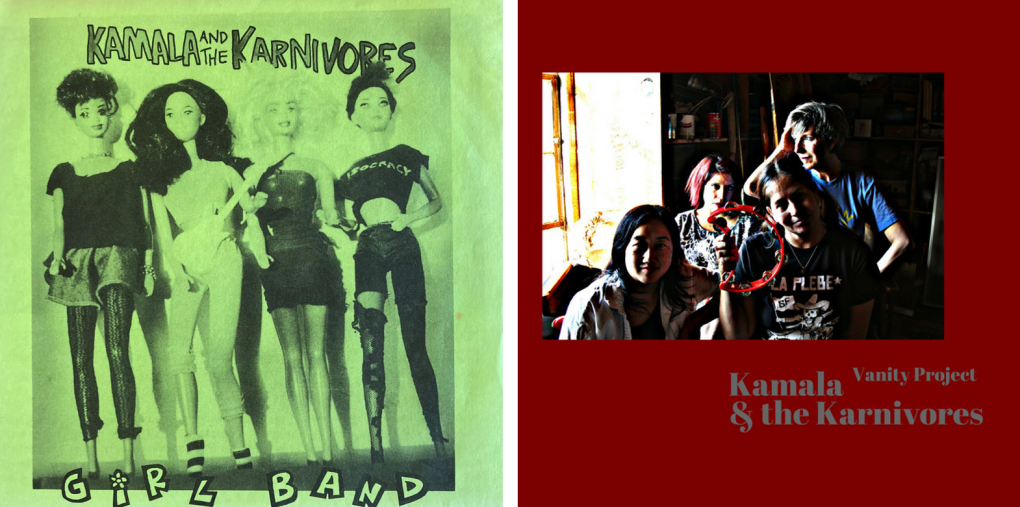

Left: Kamala and The Karnivores Girl Band EP, originally released on Lookout Records in 1989. Right: Kamala and The Karnivores second record, Vanity Project, released in 2018.

Flash forwards a couple of years, and Parks and her cofounders are sitting in a city council meeting, ready to make the case for their venue.

“The lightbulb did not go off that this sort of work was what I should be doing, not at all,” Parks said of urban planning. “I thought the city was being silly, asking things like, ‘Where will people park?’ And I said, ‘Parking? Who cares about parking!’”

Parks argued that the industrial area already had ample street parking, and most people would carpool or use transit. The majority of her friends didn’t own cars.

“We ended up rezoning the building for an entertainment permit,” she said. “At the time, it seemed like a bunch of hooey that we couldn’t have our club immediately. There was so much hoop jumping. I was definitely not inspired to pursue urban planning.”

But there was a lesson in all of it.

“The wonderful thing about youth is you’re not weighed down by past experiences that tell you what is and isn’t possible,” she said. “Fresh, questioning eyes are an asset."

After Parks “barely” graduated high school, she worked at the Peet’s Coffee and Tea warehouse and other blue collar or service jobs to prioritize and fund the unpaid efforts of touring, booking tours and shows, playing music, and volunteering at Gilman. However, part-time studying at community colleges eventually led to her getting a math degree from a four-year college. Unsure of what to do next, she got her teaching credential.

“Teaching was brutal,” she said. “I have so much respect for teachers. That is the hardest job I’ve ever had.”

Before getting the credential, Parks had taken a few urban studies classes at San Francisco State and realized, “This is it! This is what I want to do!”

But Parks wasn’t sure she wanted to spend more time in school to get a second bachelor's degree. And though she loved the field, she was sick of being poor and just wanted to start working.

Her stint as a teacher lasted about two years, and Parks took some time to regroup working as a project assistant at a construction management company. While there, she discovered the urban studies flame still flickered inside her.

Parks eventually decided to enroll in a grueling program at UC Berkeley, where she got two master’s degrees, one in civil engineering and one in city and regional planning.

She went on to work in consulting and for the City of Berkeley. BART, however, was always the dream.

Kamala drumming with Kamala and The Karnivores in 2017. Credit: Jonathan Botkin.

“BART has a very special place in my heart and has been crucial to many aspects of my life,” she said.

In 2018, after applying for years to any position she was qualified for, Parks finally got the call that she was selected for a planner role.

She's never looked back.

“There is rarely a day I wake up and say, ‘I don’t feel like going to work today,’” she said. “I just feel so lucky.”

Parks wishes she had discovered transportation planning earlier. Growing up, she never thought of it as a profession or really knew that the field existed at all. Now, she’s doing her part to amend that for the next generation.

“A few years ago, I went back to Berkeley High School for a lunch session called ‘How did you get that cool job?’ where I met with seniors and talked about what I do,” she said. “I wish someone had done that for me!”

Through it all, the punk community has remained a constant force in her life. And she’s still involved with 924 Gilman, not as a booker or board member anymore, but as an attendee and an as-needed advisor. To this day, the venue hosts more than 20 nights of performances a month, often with bills consisting of five to six bands.

Parks left an indelible mark on the Bay Area punk scene, and now, as a planner for BART, she gets to leave a different sort of legacy behind.

"Planners come up with the ideas that spur improvements to connect communities,” she said.

And that’s a through line in her life. Whether its music or street improvements, she wants more than anything to facilitate connections– to other people and to the spaces in which they gather.